Helping unpaid caregivers of dementia patients anticipate and plan for their future.

Methods

Secondary Research Cultural Probes Interviews Usability Testing

Team

Yuting Han Victor Wang

Sponsor

Premera Health

Duration

3 months

My role

I spearheaded the planning and execution of all research activities. Additionally, I contributed heavily to the product design and the development of the functional prototype.

Challenge

One of Premera's key user groups are caregivers, and this group struggles to find care for their loved ones. Premera asked us to design an impactful product that would ease some of the struggles that caregivers encounter.

Starting narrow

I'm a big believer in designing for a small group and then expanding from there, but Premera hadn't specified the segment of caregivers they were interested in designing for. So the first thing we did was conduct secondary research to find a group that satisfies Premera's business needs and also resonates with us.

Criteria for our target user group

Throughout our research, we found out that nearly half of all caregivers who provide help to older adults do so for someone with dementia. The hours spent on unpaid caregiving for someone with dementia were valued at 232 billion in 2017. A devastatingly large problem.

Data from the 2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures

This group of caregivers definitely resonated with me because my beautiful grandma suffered from Alzheimer's before she passed away, and my mom was her primary caregiver. I've seen first-hand, the stress and struggle this caregiver group goes through. With that, we narrowed down our user group to caregivers of dementia patients.

Planning our research

Goals

- Start general and learn about the overall experience of caregiving, to make sure we don't miss out on important findings that don't necessarily fit within the confines of finding care.

- Go narrower, and understand the process of finding care from a caregivers perspective and how it can be improved.

Methods

This project was for an ideation class, which meant that the generative research would have to be completed in under 3 weeks, and the rest of the project time would be spent on the other phases of design. This restricted the type of research we'd be able to conduct.

Additionally, we were required to conduct secondary research and cultural probes as part of the course deliverables. I wasn't a fan of using cultural probes (at first), because I felt like we were being asked to use them just because they're a buzz word and not because the method fits the context.

I wasn't confident that we'd be able to gain deep insights with secondary research and cultural probes alone, so I decided to fit a couple of interviews in our last week of research.

Our planned research activities

Looking for opportunities

Beginning our exploration with online observation.

The first thing we did was monitor message boards on online dementia caregiver support groups to see what the group is talking about, and hopefully find a starting point for our project. With that, we learned two things:

Caregivers are immensely stressed

Screenshots from the alzconnected online forum

Caregivers feel regretful

Screenshots from the alzconnected online forum

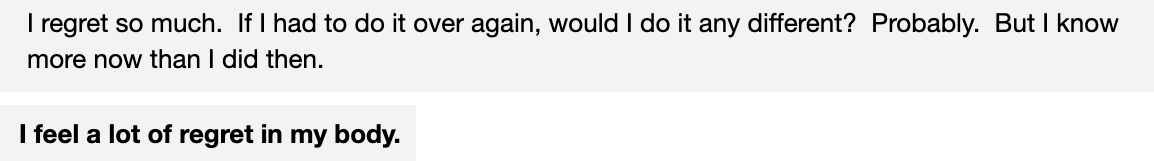

Our literature review revealed that there's no shortage of reasons behind caregiver stress and regret.

We conducted an extensive literature review to uncover where their stress and regret comes from. We were able to identify many factors. To make sense of our learnings, we mapped them into a finding care process.

Secodnary research findings mapped to the finding care cycle

Empathizing

We wouldn’t be able to focus on all the opportunity areas that we uncovered and we needed to narrow down. We decided to use cultural probes to help us understand which problems were more pressing from a caregiver's perspective. Additionally, these probes would be an opportunity for us to learn more about the caregivers before the interviews. With that, we designed our probes around two explorative questions:

- What are their major sources of stress?

- What would they do differently?

Cultural probe activities

We shared our probes in online communities and were promptly forced to rethink what we just did. As soon as the responses started coming in, we realized that we were contradicting our research findings. Our online observation had shown that caregivers are too stressed and busy to make the right decisions regarding care, yet we were asking them to sit down and complete an elaborate and time-consuming probe that requires lots of sketching and writing.

"Ah, sorry... I can't draw s*** so why would I stress myself out trying to sketch how I feel about my life and the stress I live with on a daily basis?!"

When we were asked to use probes, my mind instantly went to the original cultural probes by Gaver; elaborate postcards and maps. This might have worked for Gaver's audience, but this certainly wouldn't work for ours. I realized that rather than using the method as it originally was, we'd have to tweak it to not only fit our audience but also helps and augments them.

Picture of the original cultural probes by Gaver

We decided to take a step back and design new probes that would evoke positivity and be quick. This time, we left a box out on the street in downtown Seattle asking caregivers what they’d do differently if they could go back in time. Additionally, we designed a tear-off flyer prompting caregivers to take what they needed.

The idea behind having them out in the street was to have them be something that caregivers just stumble upon and effortlessly interact with. We asked the same questions to caregivers in dementia support groups online, because we were worried the physical probes in the uncontrolled environment, would get responses from different types of caregivers as well.

Our revised cultural probes

Narrowing down some more

Caregiver regret is a symptom of the real problem, poor planning, which leads to the wrong care choices.

Most of the responses from our probes, in one way or the other, explained that caregivers wish they would've planned better. With that, we concluded that stress is not the key problem, regret is not the key problem, planning is where things start to fall apart.

"I wish I had known more about this ugly disease before I jumped in with both feet.

We asked ourselves why someone would make the wrong choice, and concluded that it would most likely occur due to:

- Not having all the information needed.

- Evaluating the available options poorly.

With that, we decided to deep-dive into the problems they face gathering information and evaluating options.

Our narrowed focus based on our research

Digging Deeper

Getting to the root of their problems through interviews.

At this point, we felt like we had a narrow enough scope and a good understanding of our target population from the probes. We were ready to hear from caregivers about their experiences gathering information and evaluating options.

Research Questions

- How do they find information when they need it?

- How do they evaluate their different options?

- How do they know if they made the right choice?

Working around the challenges

There were two main challenges that we identified before we started the interviews. The time and resource constraints of this project meant that we could only interview 3 people. Additionally, the topic of discussion is very sensitive and hard to talk about with a stranger.

Recruit extreme users & experts

Since we could only talk to three people, we decided to recruit extreme users and experts only. We looked for people that are active in the community, so they can share their own experiences and the experiences of others. I succeeded in finding 3 participants that fit our "extreme" profile, from Facebook groups and Reddit.

Participant profile

Treat it as a conversation, not an interview

Instead of conducting a traditional in-lab session with our participants, we opted for intimate 1-1 conversations in places that they picked and felt comfortable in. We ended up conducting sessions in their homes, in cafes, and remotely.

Insights

Caregivers receive insufficient information post-diagnosis and end up going to the internet for help.

“Then people hop on the internet and that’s like trying to get a sip of water from a fire hose.”

When evaluating choices, caregivers consider the impact the choices will have on varying aspects of their lives, but the most important factor is cost.

“Cost is a definite concern, other things yeah of course, but I don’t want to lose my house.”

Caregivers rely heavily on their support community for guidance and help in making choices.

"I pick up the phone and talk to my friends from [support group name] because they’ve gone through it before"

The way caregivers feel about their choices will often change over time.

"At first I was distraught over it but now I know this was the right choice, and that that’s what he would’ve wanted.”

Paving the way for design

Framing the Problem

How might we bridge the information gap to help caregivers understand the immediate and future impact of their choices?

We learned from our research that there's no "right choice" that caregivers can make, a choice that they're at peace with today, might turn into something they regret in the future when the circumstances change.

We had to accept that and realize that all we could do is provide them with enough information to see the impact their choices will have on their present lives, and shed some light on how things may change in the future.

Design principles

Lean on the community: The design should leverage the strong community of caregivers who go to each other for support and advice.

Inform but don't overwhelm: The design should give caregivers just the right amount of information that they need to know without overwhelming them.

Facilitate reflection: The design should encourage reflection about decisions and allow for corrective actions.

Introducing CareWizard

After a lot of ideation and prototype testing - which I'm skipping so not to bore you with too long of a portfolio piece, we ended up with CareWizard. It's a platform where caregivers can explore the major care choices they’re gonna need to make, and the impact these choices will have on different aspects of their lives, such as cost, marriage, and social life.

Once care decisions are made, caregivers can find action plans to help them take action towards making their choice a reality.

Finally, my favorite part of CareWizard is that it leverages the strong caregiving community by using the past experiences of caregivers to help other caregivers predict their future more accurately. Caregivers are asked to provide feedback about how decisions impacted them, and how they reflected about that choice over time. It's for caregivers, by caregivers.Impact

Increase the caregiver’s decision-making confidence: Caregivers feel more comfortable making decisions because they have the key information that they need, they can see the impact of their choices, and they know how their feelings towards the decision could change over time.

Increase the caregiver’s trust in Premera: Caregivers can see data about costs collected from other caregivers. Additionally, they can see the cost data provided by Premera. This will help caregivers compare between the different sources of data and foster trust.

Reflecting

Takeaways

User research leads to a better design ethic. Front-facing the caregivers made me a lot more aware of everything I was designing, and constantly thinking of the implications of the design. I think all project stakeholders should be involved in user research because that's how they'll develop empathy and design ethically for the user.

Tweak your methods. Despite being against using cultural probes at first, they actually turned out to be really valuable. I think that's because rather than use the method in its original form, we tweaked it to fit our context.

When life gives you lemons, talk to extreme users. Only talking to three participants is not ideal. But, I think we did the best we could, given the time and resource limitations. We were aware that the limited interviews could lead to false insights, and as a result, we validated all of our findings through secondary research as well.

Limitations

The caregiver group was not narrow enough: Our solution could have been more powerful if we keyed in on a more specific group within dementia caregivers, for example, caregivers of husbands or caregivers of mothers.

The primary research was not extensive enough: We learned a lot from the 3 interview sessions that we conducted, and I'm sure we would've learned much more if we talked to more caregivers.